Shooting Power: The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964)

By Kia Khalili Pir

This review contains minor spoilers

How do you shoot Power? In other words, how do you make your audience aware that they are witnessing an expression of superiority without explaining it through words or sounds? Because, in a discussion among friends, I could just tell you: “Look at that man standing before the one kneeling on the floor, look, that is power right there!” In the same way, in a movie, you could just have one of the characters have the same conversation with someone else. Or you could help yourself with the use of music: adding an epic soundtrack in the right places and hoping that the audience will understand what you are trying to convey.

But what if we had to show Power, without using talking heads and sound? How can we, then, represent Power visually? Our brains are naturally wired to make connections, so we witness a man kneeling before another standing before him, and we immediately assume that the man standing is superior to the one kneeling. He is therefore powerful. In the same way, there is a cinematic vocabulary that can be used to translate the idea of Power to the spectators.

And what better way to write about the representation of Power than a movie set in Ancient Rome? A period in history, and its accompanying cinematic genre, that so intrinsically deals with the portrayal of authority, in all its glory and decadence.

The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) by Anthony Mann was a massive flop when it first premiered, both critically and financially. It earned a niggardly $4.75 million against a $19 million budget, with veteran film critic Crowther Bosley calling it “massive and incoherent,” and an “above-average historical drama.” And if that was not enough, the movie pretty much—and quite ironically, given the title—annihilated the Roman epic genre in Hollywood and single-handedly bankrupted the production company of producer Samuel Bronston. Only decades later, thanks to the savvy direction of Ridley Scott’s spectacle Gladiator (2000), was Ancient Rome successfully brought back to life on the big screen. Which prompted a subsequent string of mostly awful derivatives and a few great spawns in the smaller medium—namely the HBO TV series Rome in 2005.

Despite its initial fiasco, The Fall of the Roman Empire has since been reappraised, with some people even considering it the most sophisticated of Roman epics (Winkler, 1995: 139). Set at the end of emperor Marcus Aurelius’ life (Alec Guinness) and during the short-lived reign of his son Commodus (Christopher Plummer), the film mixes historical facts with fiction bringing on screen the story of ad-hoc-created character Gaius Livius (Stephen Boyd), the emperor’s pupil and general, as he struggles to survive in an empire on the verge of collapse. After a gruesome shift of power, Livius, now loathed by Commodus, finds himself chased by the emperors’ men, and forced to fight in order to protect his life and that of beloved Lucilla (Sofia Loren). For an epic, the Fall is quite intimate, filled with complex characters, thoughtful dialogues, and bold storytelling decisions.

The visual vocabulary Anthony Mann employed to represent Power on screen is recurring in other Roman epics, examples of which can be found in such movies as: Julius Caesar (1953), Ben-Hur (1959), Spartacus (1960), Cleopatra (1963), and, most recently, Gladiator and the TV series Rome. The same vocabulary has also been used in movies belonging to other genres like The Godfather (1972) and Parasite (2019), just to name a few. It is thus important and useful to study it, both as a tool for filmmakers to better their skills and knowledge of the craft, and as a paragon for connoisseurs to judge other films against. This vocabulary is composed of:

Framing

Blocking, Staging, and Popular Acclamation

Use of props, costumes, and sets

Death scenes

A scene from the film

Framing

The most intuitive way to cinematically shoot Power must be through the framing of the powerful subject. In other words, with the camera. The choice of lenses in this case is secondary since nobody can truly say that a 35mm lens accomplishes much in shaping the perception of someone’s social status to the audience. Nor does the lighting, for the same reason. Someone could argue that a character, if lit correctly, can come off as menacing, but, truly, manipulating the viewer’s perception of a character boils down to the angle of the camera and its movement. The way the audience sees the subject influences their feeling of the subject. And we use the word “subject” because Power can also be associated with objects like buildings, thus the rules that apply to framing humans can also apply to the framing of a castle, for example. Nevertheless, in this particular instance, we will be talking about the framing of Livius when he first comes in contact on screen with emperor Aurelius.

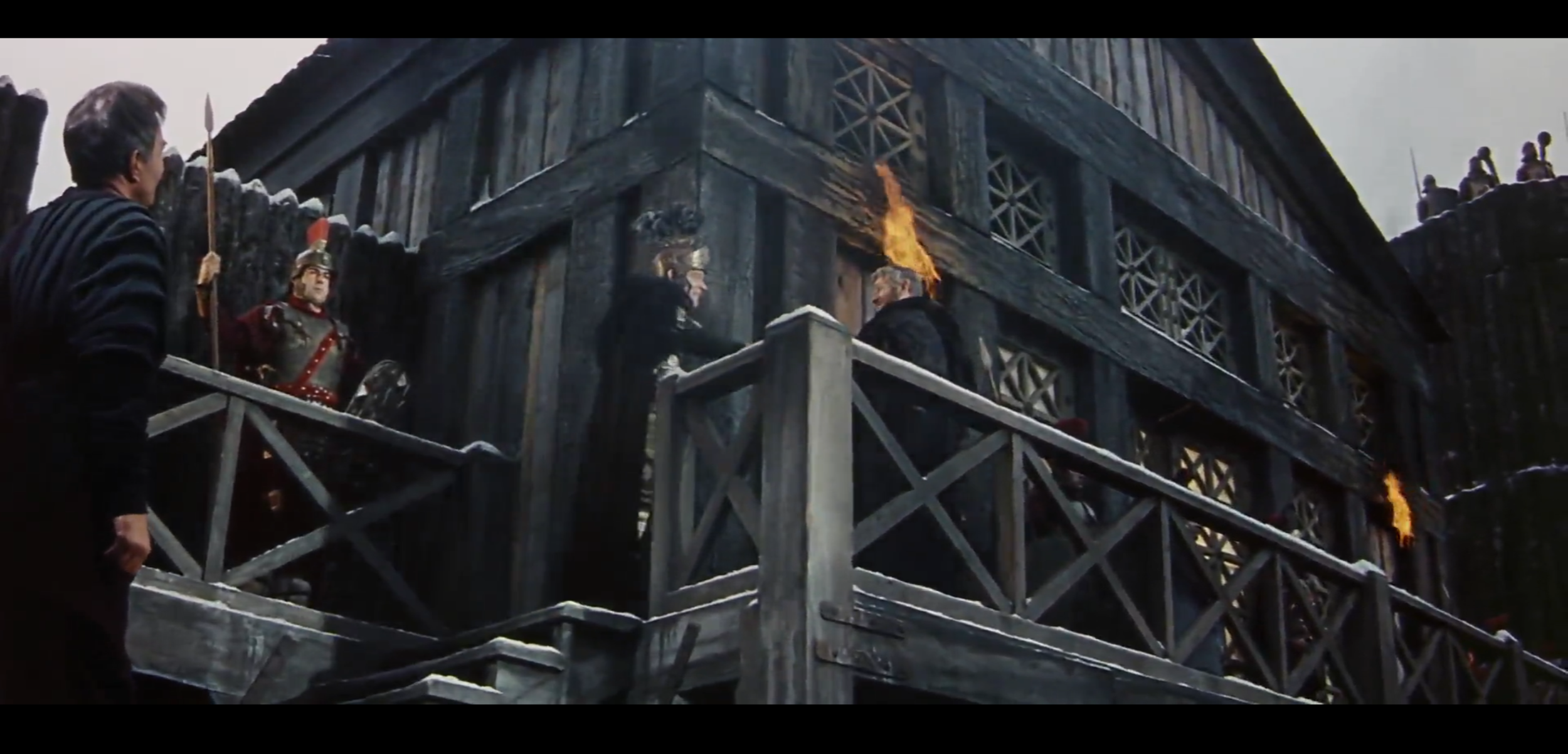

As the war against the German tribes rages, the loyal and charismatic general Gaius Livius arrives with his troops at the border fortress—the temporary abode of the emperor—eager to meet with Marcus Aurelius and reunite with the ruler’s daughter Lucilla. As he climbs the ladder to the royal lodgings, Livius meets the old Greek libertus Timonides (James Mason), the emperor’s deputy and philosophical guide. As they jovially talk, however, the emperor, who had been eavesdropping the conversation, brusquely interrupts them to greet Livius. Livius then walks up the stairs to finally salute Caesar.

The movie was shot by Cinematographer Robert Krasker with a 70mm Ultra Panavision camera using anamorphic lenses in order to convey the epic grandeur of the film genre and of the Roman Empire. The 70mm print—twice the size of the standard 35mm—captured in great detail awesome sceneries and battles, while the anamorphic lenses horizontally squeezed the image to make it wider. Mann was not trying to depict the story of an individual, but rather of a civilization that “destroys itself from within (Mann in Winkler, 2009: 132).” But if the Ultra Panavision was perfect for photographing an immense army or the fall of an empire, at the same time the wide aspect ratio (2.76:1) made it difficult to photograph intimate conversations and to quietly depict Power when it is subtly present in the scene. Moreover, during their first exchange Aurelius only wears a big, anonymous black coat, while Livius displays an elaborate armour and a crested helmet, and is treated with respect by Timonides. Yet, even with muted audio, the relations between the characters on screen are clear: both the general and the libertus are socially beneath the man who lastly joins the conversation. How did the Director and Cinematographer obviate these issues: the wide aspect ratio and lenses that impair capturing intimacy on screen, and the lack of a wardrobe that quickly establishes the status of the characters? With the low-angle shot—a shot purposely concocted to make the framed character look bigger by positioning the camera below their eyeline and looking up at them.

When Livius arrives at the ladder, the camera captures him from a low-angle; as he proceeds up the steps the camera tilts up, showing both Timonides and the emperor, although the latter is unnoticed by the other two. As Aurelius prepares to interrupt them, he moves closer to the center of the frame. Although he stays quiet in the background, we are naturally drawn to look at him. Finally, the camera tilts and jibs up as Livius climbs the stairs, not only implying that his goal is to reach the top, but also showing whom already is at the top.

Livius arrives at the ladder

Livius mees Timonides as Aurelius eavesdrops on the conversation

Aurelius interrupts the conversation. Everyone looks up at the emperor

Livius walks upstairs to meet Aurelius

Due to aspect ratio and the lenses, the shot feels huge as Marcus Aurelius towers above his two most trusted men. What we have here is the use of a common shot integrated with the movement of the camera and the movement of the actors (“blocking,” which we will talk about later). Mann then incorporates the magnitude of the scenery photographed by the anamorphic lenses with the use of the low-angle shot to convey the gravitas, the position of extreme influence that Aurelius fills.

Throughout the movie the director resolves to low-angle shots when photographing the relationship between a powerful man and his subjects: when Aurelius is acclaimed by his army to the cry of “Hail Caesar!”, for example, or analogously when the new emperor Commodus interacts with one of his men, who had been sent back to Rome in a cage.

If one wishes to look at a modern use of the same shot, they can watch Parasite by Bong Joon-ho. When Ki-woo first arrives at the Park residence, he walks up the stairs that lead to the house in similar fashion as Livius. Having seen where the Parks live, it becomes immediately evident that they are richer than him, which automatically makes him feel inferior to them. Alternatively, for a less complicated version of the low-angle shot, refer to the iconic shot of Darth Vader menacingly treading the corridors of the Death Star in Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977).

Parasite (2019). Ki-woo walks up the stairs

Star Wars (1977). Darth Vader makes his entrance

Blocking, Staging, and Popular Acclamation

Blocking in film refers to the positioning of the actors in the shot, where and how they move, but mostly how they interact with each other. Staging, on the other hand, commonly describes the action of choosing where to put the camera and where the props. Thus, popular acclamation, which is performed by the enthusiastic Roman people or the chanting soldiers, falls ambiguously between the two definitions: it is both a form of blocking and staging. All these three are used by Mann to great effect.

If Alfred Hitchcock tightly controlled the movement of the actors—referring to them as “cattle”—Mann preferred a more relaxed approach to blocking, if still deliberate. He would often invite actors to interact with both their surroundings and the other players to capture the more natural performances. On other occasions, his direction of their movements would be more particular. At one point, Commodus, now emperor, is talking to his senators in the curia when he nonchalantly walks over the map of Italy. Through his actions alone his motives are clear: he does not care for the Italian tribes and he is now the supreme authority in the empire. In this moment, the camera even tilts down to his feet to emphasize his gesture.

There is no need, oppositely to what contemporary movies often seem to indicate, to spell out every piece of information through dialogues and voice-overs: a careful blocking and staging keeps the viewer’s mind much more engaged, as they, without explicit guidance, process the information they are given. In general, when directors approach blocking, they should be thinking, “What is the character’s motive?” “What is the scene about?” and “What does the character want?” Just trying, then, to show, rather than tell these points, will make the narration much more interesting and stimulating. When dialogues can be replaced by actions, it can be worthwhile for the film to at least explore the possibility of doing so. The staging, then, ought to be approached in the same way and, when properly accomplished, will emphasize the point the director is trying to make.

In a wide-angle shot, Commodus stands on the map of Italy

Camera tilts down as Commodus dances on Rome

So Commodus dances on the map of Italy to underline his power over the entirety of the Roman Empire and Livius climbs the ladder to reach the trusted Timonides, before having to move forward to speak with Aurelius. None of the characters appear on the scene at the same height, and even though Livius is the emperor’s general, Timonides, who is more of a spiritual guide for Aurelius—field the emperor favors over warfare—occupies a higher position and is superseded only by the most powerful individual in the scene, Caesar. Commodus, on the other hand, is the leader who threatens to massacre whomever will stand in his way while joking around in the senate. The camera captures the scene, the angle denotes the status of the characters involved, and the movement of the actors sells that status.

When we are first introduced to Marcus Aurelius as an emperor, it is through a low-angle shot as Livius walks up the stairs to meet him. When Commodus is brought forth in the senate as the new sovereign for the first time, framed with a low-angle shot, he stands up from the throne and tip-taps on the empire. If Aurelius was emperor, he was emperor surrounded by friends like Timonides and Livius; Commodus stands alone.

Through meaningful staging, blocking, and framing, the audience can thus witness the difference between two types of the same Power.

Aurelius greets Livius while Timonides looks on

Commodus stands in the curia

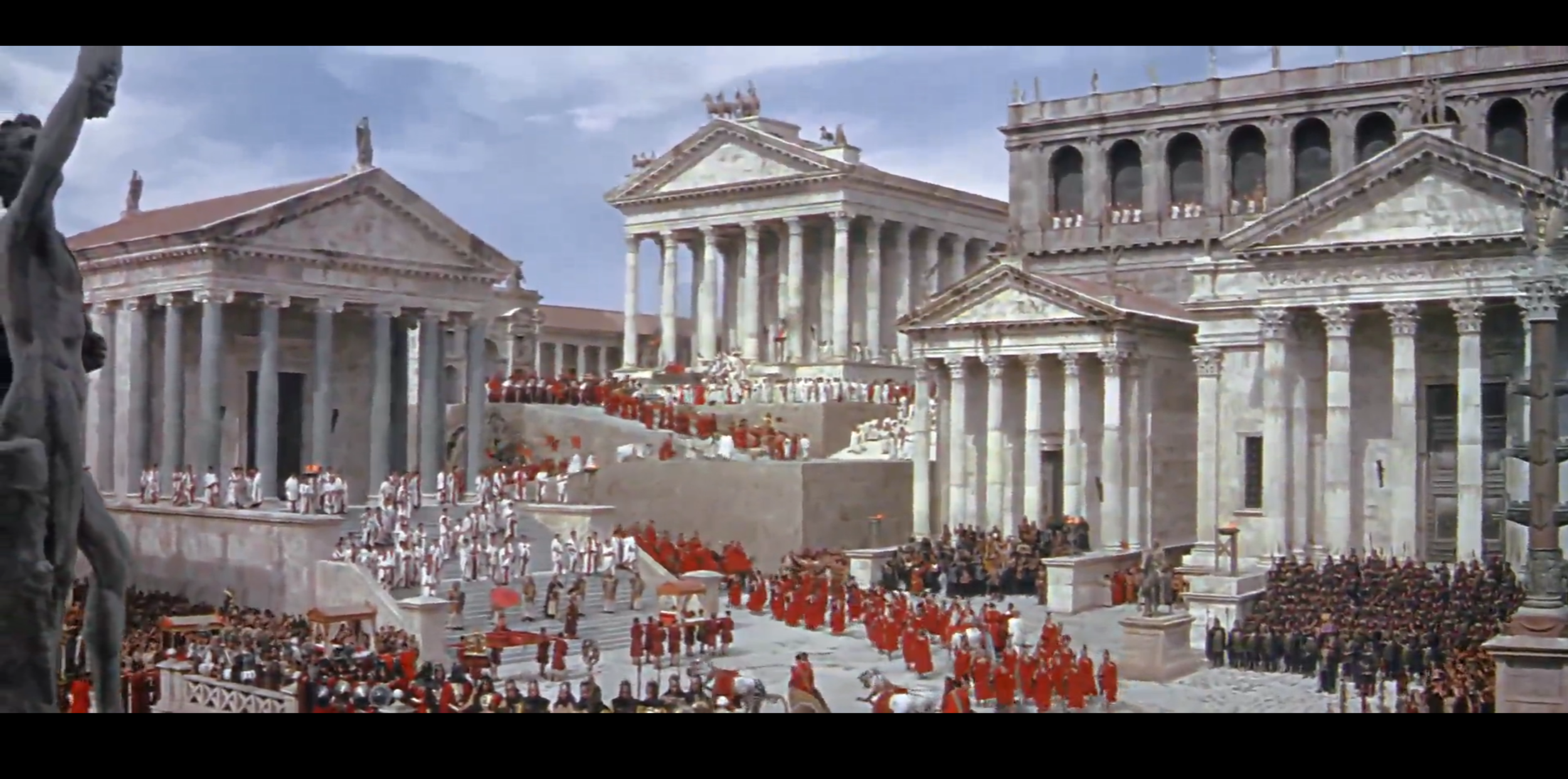

Popular acclamation plays an equally important role. Early on in the movie, the various kings and tribe leaders loyal to Rome arrive at the border fortress to listen to the emperor. What adds gravitas to the figure of Aurelius is the joyous and enthusiastic response he receives at the end of his declamation. After Aurelius’ death, when Commodus enters Rome in triumph, he is hailed by its citizens, who recognize him as the new emperor. Thus, the mob and the army are both instruments to measure Caesar’s influence. On screen, with their chants and screams, they transmit to the viewer a clear message: the ruler comes first. They provide an audience for Power, where the occasion is the stage, and the emperor the sole actor. Mann depicts the army to emphasize the concept that in Ancient Rome, imperial power depended on military power, and also to underline the status of the characters featured in the scene. He shows the mob to give resonance to the figure of the emperor. It is actually a simple and straightforward cinematic device: if you want your spectators to think that someone is important, just have people in the scene show their open support to them.

Commodus waves at the chanting crowd and the army

Use of Props, Costumes, and Sets

An insoluble component of the mise-en-scène is the props, the costumes, and sets. They are all instruments to bring the world of the story alive: they can translate an idea to the spectators, they can underline someone’s status on screen, and they provide invaluable help to the actors. In preparation for his role of Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy (1982), Robert De Niro stated that the key to the character came from its wardrobe, which he saw on a mannequin while researching the role. He was especially particular about the shoes Pupkin should wear. During the filming of Interstellar (2014), Director Christopher Nolan went to great lengths to use as many practical effects on set as possible. An expedient that both Matthew McConaughey and Anne Hathaway found extremely helpful for their respective performances. Regardless of one’s opinion about Stanislavski’s Method and his definition of “truth” in acting, just on a practical level, actors will always favor using props in the scene instead of their imagination. This both adds dynamism to the performance and anchors it in reality. The wardrobe not only helps the players flash out the character, but also functions as a visual cue for the audience to know what kind of person they are looking at and the period and setting of the story. In movies, most often than not, one can judge a book by its cover when it comes to character. On the other hand, the setting adds to all the above and defines where the story takes place.

In the Fall, Mann let the actors interact with the various architectural features of the palace and the props, using them to visually expound the emperor’s standing. Thus, we see Commodus boastfully stomping on the map of Italy, while musing about slaughtering and subjugating the dissidents and the barbarians, or sitting on a throne in the curia to remind the senators (and the viewers) of his socially and politically superior position. Equally important are the dining scenes, during which Commodus indulges in food, wine, and sex. This display of riches, directly brought upon by power, underlines Commodus’ higher standing, especially when confronted with Livius’ more humble condition.

Commodus berates a slave who fled from his advances, while Livius looks at the scene inert

When it comes to the wardrobe of the emperor, Aurelius shows a clear disregard for fancy and opulent clothes—a reflection of his Stoic beliefs—preferring instead more sober outfits, like a dark brown toga or a black coat. Mann therefore decided to concentrate more on reflecting Caesar’s personality and creed, rather than his persona. However, Commodus is more explicit as a symbol of power. Since his first introduction, he wears ostensibly multi-colored clothes, adorned with golden, wolf-shaped embellishments. Once he becomes emperor, he dresses even more lavishly: he starts wearing a crown and dark red robe with golden decorative linings. Although he is surrounded by senators in their luxurious togas with one red stripe or by the Praetorian Guard dressed in crimson, Commodus is still easily recognizable as representative of the sole, unchallenged authority.

The movie also boasts the biggest and most sophisticated recreation of the Roman Forum in cinema history, with a 92,000 square meters outdoor set—the largest ever built. This meticulous and faithful replica shows us Rome at the height of its strength and elegance. By introducing it to the audience with Commodus’ triumphal entrance, Mann links the viewers’ perception of Rome with the idea of absolute power—a Power that is, however, corrupted and ephemeral because it is embodied by a bad emperor. This also emphasizes the beginning of the fall, which occurs at the end of the movie.

Similarly, the interior sets display all the riches and luxury which come with position of “first in Rome,” and were designed to “create a tangible rhetoric of power, a panegyric in architecture (McDonald, 1982: 71)”: they are a memento of the indissoluble influence of the princeps (the Latin expression for “emperor”), which ought not to be questioned nor fought.

The Roman Forum as first shown with Commodus’ triumph

Death Scenes

Death portrayed on screen both symbolizes a change in or the end of power. Perhaps incorrect from a semantic point of view—when one loses power they cannot be powerful, so there is nothing to represent—in movies the matter is different and less philosophical, as death scenes help both from a narrative point of view (the audience knows that ding dong the king is dead) and to throw into sharp relief who now has the power and who does not. Marcus Aurelius’ murder marks a turning point both in the story and in the dynamics and lives of the characters that survived him. Livius loses a friend and his most powerful ally, Timonides is destroyed, Lucilla mourns a father, but, mostly, Commodus gains an empire. The death of Caesar effectively sets in motion all the dramatic events that will occur later, as Commodus, now resentful towards Livius and his father, distorts Aurelius’ dream of a Rome united and in peace into a corrupted, absolutist vision of power entirely concentrated under him. In doing so, he ironically signs the fate of Rome. Livius assassinates Commodus and Rome begins its unstoppable demise, having lost its only landmark. Commodus’ death leaves the senators first to bribe Livius into becoming the new princeps and—after his refusal—to bicker with each other for the position of emperor. As Livius and Lucilla depart, the ominous voice-over reveals that the subsequent animosity that spread among the senators, the conflicts with the barbarian tribes, and the various struggles for the throne eventually led to the Empire's collapse.

Death thus provides an emotional and dramatic milestone, functioning as an unforgiving and final turning point in the plot after which all has irrevocably been altered. Power has irrevocably changed hands. Like The Godfather, like The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), like The Fall of the Roman Empire, when the emperor is dead, all hail the new emperor.

So how do you shoot Power? How does a great director like Anthony Mann show Power cinematically? He frames the powerful subjects with a low-angle shot, underlines their superior status with meticulous blocking, has a bunch of people chanting their names, uses props, costumes, and sets to ground them in their position, and shows them dying. Mann tapped into the existing visual vocabulary and applied it to the world of Ancient Rome as it was later applied by other competent directors to The Godfather, Star Wars, and Parasite. This vocabulary exists for a reason and studying it—as well as mastering it—will prove a worthwhile endeavor for any filmmaker out there.

When The Fall of the Roman Empire came out, it marked the end of the Roman epic genre in Hollywood. About thirty years later, Gladiator was deeply influenced by the film and brought the genre back. If that is not Power, then I do not know what else is.

Acta est fabula, plaudite!

—Augustus

*All pictures belong to Samuel Bronston Productions and Paramount Pictures and are intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and non commercial purposes only.

**Bibliography:

M. Wyke, Projecting the Past Ancient Rome, Cinema and History, London (1997).

R. Burgoyne, The Hollywood Historical Films, New Jersey (2008).

D. Landau, W. Parks, J. Logan, R. Scott, Gladiator: The Making of the Ridley Scott Epic, New York City (2000).

W. W. Briggs, Jr, ‘Peace and Power in The Fall of the Roman Empire’ in M. M. Winkler (ed.) The Fall of the Roman Empire Film and History, Oxford (2009), pp. 225-240.

A. Mann, ‘Empire Demolition’ in M. M. Winkler (ed.) The Fall of the Roman Empire Film and History, Oxford (2009), pp. 130-135.

M. M. Winkler, ‘Gladiator and the Colosseum: Ambiguities of Spectacle’ in M. M. Winkler (ed.) Gladiator Film and History, Oxford (2009), pp. 87-110.

D. S. Potter, ‘Gladiators and Blood Sport’ Spectacle’ in M. M. Winkler (ed.) Gladiator Film and History, Oxford (2009), pp. 73-86.

J. Solomon, ‘Gladiator from Screenplay to Screen’ in M. M. Winkler (ed.) Gladiator Film and History, Oxford (2009), pp. 1-15.

W. L. McDonald, The Architecture of the Roman Empire. Vol. 1: An Introductory Study, rev. ed. New Haven and London (1982).

B. Crowther, ‘Screen: Romans Versus Barbarians: Spectacles and Melees in 'Fall of Empire'’, The New York Times 27 March 1964.

Kia Khalili Pir was born in Verona, Italy, and does his best to be a good writer and film director. He is a trained classicist who graduated from the King’s College of London and now resides in the Old Smoke. Apart from movies, he enjoys chess, boxing, and getting angry at modern technology.